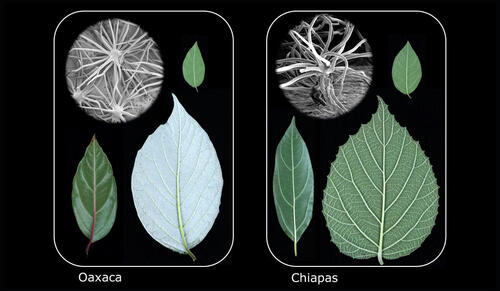

Evolution has long been viewed as a rather random process, with the traits of species shaped by chance mutations and environmental events — and therefore largely unpredictable. But an international team of scientists led by researchers from Yale University and Columbia University has found that a particular plant lineage independently evolved three similar leaf types over and over again in mountainous regions scattered throughout the neotropics. The findings provided the first examples in plants of a phenomenon known as “replicated radiation,” in which similar forms evolve repeatedly within different regions, suggesting that evolution is not always such a random process but can be predicted. The study is published July 18 in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

“The findings demonstrate how predictable evolution can actually be, with organismal development and natural selection combining to produce the same forms again and again under certain circumstances,” said Yale’s Michael Donoghue, Sterling Professor Emeritus of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology (YIBS Affiliate & former Director) and co-corresponding author. “Maybe evolutionary biology can become much more of a predictive science than we ever imagined in the past.” For the study, the research team studied the genetics and morphology of the plant lineage Viburnum, a genus of flowering plants that began to spread south from Mexico into Central and South America some 10 million years ago. Donoghue studied this same plant group for his Ph.D. dissertation at Harvard 40 years ago. At the time, he argued in favor of an alternative theory in which large, hair-covered leaves and small smooth leaves evolved early in the evolution of the group and then both forms migrated separately, being dispersed by birds, through the various mountain ranges.

“This collaborative work, spanning decades, has revealed a wonderful new system to study evolutionary adaptation,” said Ericka Edwards, Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Yale (YIBS Affiliate) and co-corresponding author of the paper. “Now that we have established the pattern, our next challenges are to better understand the functional significance of these leaf types and the underlying genetic architecture that enables their repeated emergence.” Edwards and Deren Eaton of Columbia are co-corresponding authors of the paper. For more information, please click here for an article published by Yale News.